Set-Point Theory: Exploring Weight Regulation

Content note: This blog discusses calories and weight loss. Please read with care and skip this post if this topic does not feel supportive for you right now.

Set-point Theory is a theory that offers a science-based explanation for why weight loss is nearly impossible to sustain and why the body actively resists prolonged restriction. Rather than viewing weight changes as a matter of discipline or willpower, set-point theory helps us understand weight regulation as a biological process shaped by genetics, history, and physiology.

In a culture that places so much emphasis on weight control, this framework can feel uncomfortable or even threatening. But understanding how the body truly responds to restriction can be both relieving and empowering.

What is Set-Point Theory?

Set-point theory suggests that the body has a natural weight range where it functions optimally. This range is not a single number but a span that the body actively works to defend.

When weight moves outside of this range, the body initiates physiological responses designed to restore balance. These responses are not conscious decisions. They are automatic survival mechanisms.

Factors that influence a person’s set-point range include:

Genetics

Dieting and weight cycling history

Hormonal changes (puberty, pregnancy, menopause)

Chronic stress

Aging

This helps explain why people can eat similarly and maintain very different body sizes, and why repeated dieting often leads to weight regain.

Why the Body Resists Weight Loss

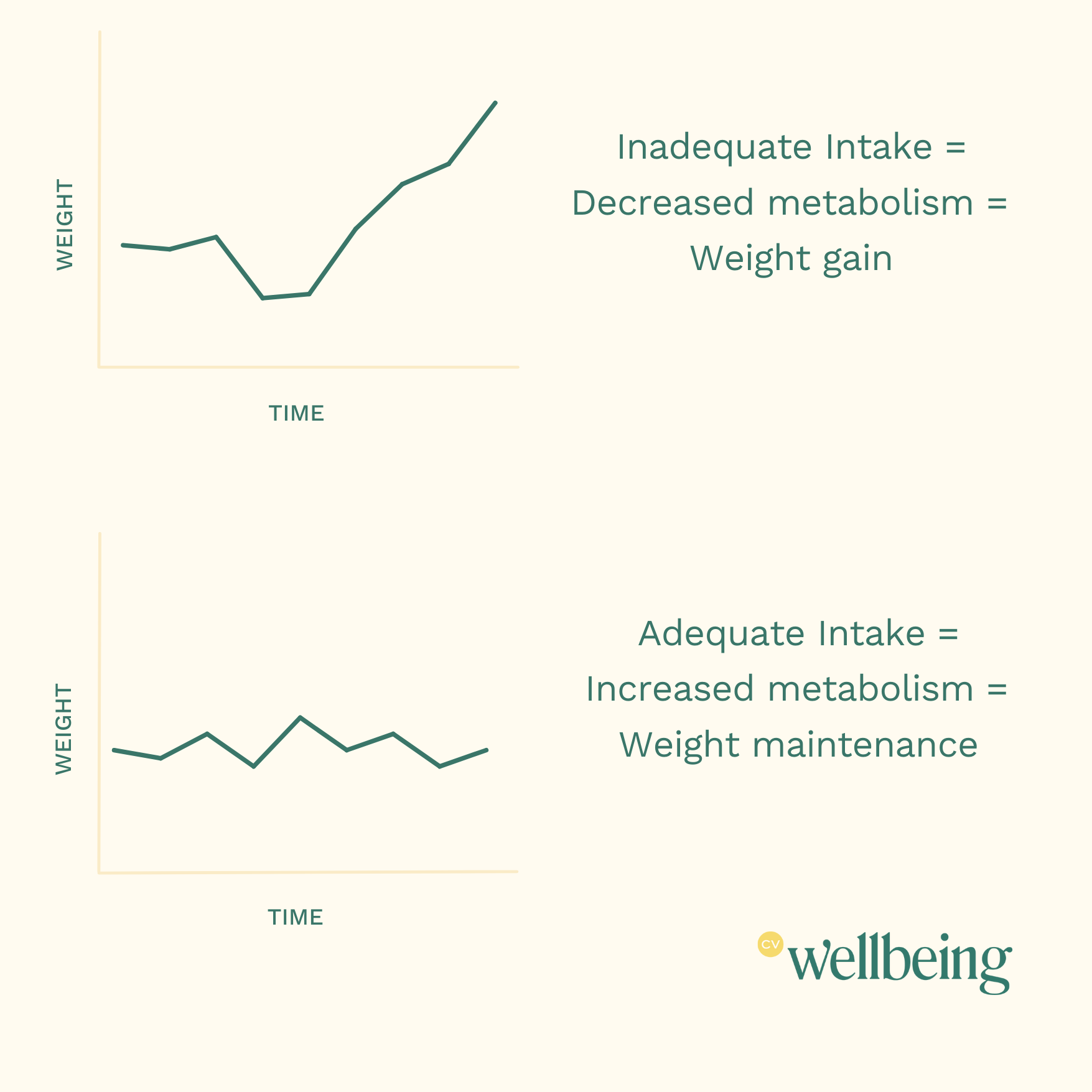

When the body perceives energy intake as insufficient, it does not interpret this as a lifestyle choice. It interprets it as a threat to survival. In response, the body activates compensatory mechanisms aimed at conserving energy and restoring weight.

How Much Can the Body Adapt Its Metabolism to Restriction?

When body weight decreases, some drop in metabolism is expected simply because a smaller body requires less energy. However, research consistently shows that the body also reduces energy expenditure beyond what would be predicted by weight or muscle loss alone. This phenomenon is known as metabolic adaptation or adaptive thermogenesis.

In controlled human studies on metabolic adaptation, researchers found:

A 5–15% reduction in resting metabolic rate (RMR) during periods of sustained calorie restriction

In some cases, metabolic adaptation accounts for 30–50% of the total metabolic slowdown, independent of body size changes

This means the body becomes more energy-efficient as a protective response. This is not a flaw. It is the body doing its job.

Metabolism Slows During and After Weight Loss

Research following individuals through weight loss and into weight maintenance shows that metabolic adaptation often persists even after eating increases.

In studies where participants lost roughly 10–16% of body weight, researchers observed:

A 5–10% suppression of resting metabolism beyond predicted needs

Continued metabolic suppression even after weight stabilized

Hormonal Adaptations to Restriction

-

Ghrelin, commonly known as the "hunger hormone," is a key player in appetite regulation. Produced mainly in the stomach, ghrelin sends signals to the brain to increase hunger and stimulate food intake. Ghrelin levels naturally rise before meals and decrease after eating, making it essential for understanding hunger cues

-

Leptin, also called the "fullness hormone," is a hormone secreted by fat cells that helps regulate energy balance by reducing appetite. It communicates with the brain to signal when the body has enough stored energy, helping to prevent overeating. Leptin resistance, a condition where the brain stops responding to leptin signals, can contribute to weight gain and difficulty feeling satisfied after meals.

-

Cortisol is a stress hormone produced by the adrenal glands that impacts numerous bodily functions, including metabolism, blood sugar regulation, and inflammation. Often referred to as the "stress hormone," cortisol is released during times of stress to prepare the body for a fight-or-flight response. However, chronic high cortisol levels can disrupt hunger cues, lead to increased cravings.

Metabolic adaptation does not happen in isolation. It is accompanied by predictable hormonal shifts.

During restriction:

Ghrelin (hunger hormone) increases

Leptin (satiety hormone) decreases

Cortisol (stress hormone) rises

These shifts increase hunger, reduce feelings of fullness, and make it harder to feel satisfied, even after eating, making sustained restriction increasingly difficult.

Additional Physiological Changes During Restriction

Restriction triggers a whole-body survival response, not just changes in metabolism.

Thyroid Hormone Suppression

The body reduces conversion of T4 to active T3, lowering metabolic rate and contributing to fatigue, cold intolerance, and brain fog, even when labs appear “normal.”

Reduced Non-Exercise Activity (NEAT)

Spontaneous movement, fidgeting, and postural activity decrease unconsciously, conserving additional energy without awareness.

Reproductive Hormone Suppression

Low energy availability can disrupt estrogen, progesterone, testosterone, ovulation, and menstrual cycles at any body size.

Nervous System Shifts

Restriction pushes the body toward sympathetic (fight-or-flight) dominance, increasing anxiety, sleep disruption, and gastrointestinal symptoms.

Digestive Changes

Gut motility slows, contributing to bloating, constipation, early fullness, and discomfort, which are often misinterpreted as “food intolerance.”

Bone and Immune Effects

Low energy availability impairs bone formation and immune function, increasing risk for stress fractures, illness, and delayed healing.

Cognitive and Emotional Changes

Restriction affects concentration, flexibility of thinking, emotional regulation, and decision-making, making food rules feel harder to challenge.

The Minnesota Starvation Experiment: A Powerful Illustration

The Minnesota Starvation Experiment (1944) demonstrated how profoundly the body and brain respond to restriction. 36 men were put on a restrictive diet of 1,400-1,600 calories/day (*Note: I find this interesting; this is not typically the calorie range that you may perceive as starving) and experienced:

Significant metabolic slowing

Intense preoccupation with food

Emotional changes and rigidity

Persistent effects long after refeeding

Men began reading cookbooks obsessively, dreaming about food, and considering careers involving cooking. While extremely unethical, this study provided valuable insight into what happens when people undereat. Modern imaging studies confirmed these effects, showing increased brain activity in reward and attention centers during calorie deprivation.

How the Body Responds to Perceived Scarcity

When food intake is uncertain, the body responds by:

Conserving energy

Increasing hunger and food-seeking behavior

Enhancing the reward value of food

Prioritizing survival over comfort and reproduction

From an evolutionary perspective, these adaptations make a lot of sense. For centuries, the biggest threat to humans’ survival was starvation. These mechanisms evolved over time for protection. In a modern dieting context, this often leads to distress and rebound weight gain.

Finding Your Set-Point Weight

There is no formula, chart, or BMI category that determines set-point weight. Research suggests approximately 70% of weight regulation is genetic, similar to height (height is 80% genetic).

Signs someone may be near their set point include:

Stable labs (when no underlying illness is present)

Consistent hunger and fullness cues

Stable energy levels

Weight maintenance without constant effort

Effortless maintenance means not tracking calories, restricting foods, compensating with exercise, or constantly thinking about food.

Set-Point Weight and BMI

Being within a “normal BMI” does not guarantee adequate nourishment. Research shows that many individuals experience hormonal suppression and symptoms of starvation while still falling within BMI-defined ranges.

This is one reason BMI is a poor proxy for health.

Can Set-Point Weight Change?

Set-point weight is not fixed forever, but it is resistant to intentional manipulation. Chronic dieting and weight cycling may actually raise the defended weight range over time. This is why repeated dieting often becomes less effective and more distressing with each attempt.

Set-Point Theory FAQs

-

Set-point theory suggests that the body has a natural weight range it works to maintain. When weight falls outside of this range, the body activates biological responses to bring it back, including changes in metabolism, hunger hormones, and energy expenditure.

-

No. Set-point theory does not mean weight is fixed or predetermined. It means the body has a defended range influenced by genetics, life stage, stress, and nutrition history. Weight can shift, but sustained changes often come with biological resistance.

-

When the body senses prolonged energy restriction, it adapts by:

Lowering resting metabolism

Increasing hunger signals

Reducing spontaneous movement

Enhancing the reward value of food

These responses are designed to protect against starvation, not to sabotage efforts.

-

Yes. The body’s protective responses to restriction occur across the weight spectrum. People can experience metabolic, hormonal, and neurological signs of undernourishment at any body size, including within BMI-defined “normal” ranges.

-

No. When adequate and consistent nourishment is restored, the body works toward stability, not endless weight gain. Weight may change during this process, but the goal is metabolic and hormonal balance, not perpetual increase.

Moving Forward With Set-Point Theory

Set-point theory offers a compassionate explanation for why dieting so often fails and why bodies deserve trust rather than control. Restriction is not a neutral act. It triggers predictable, coordinated survival responses across nearly every system in the body. Understanding this can reduce shame, self-blame, and the pressure to override biological signals in pursuit of weight loss.

If you want support exploring set-point theory, intuitive eating, or weight-inclusive care, our Registered Dietitian Nutritionists at CV Wellbeing are here to help. Reach out to begin building a relationship with food that supports both physical and mental health.